In a previous article, I shared a lesson from my early days at Amazon: moving search out of the primary database and into a dedicated search index improves both search performance and database stability. However, this introduces a new challenge. How do you keep your search index in sync with your database in a timely and consistent manner without hurting production traffic? That's what we'll explore in depth in this article. If you prefer a condensed overview before diving deep, see Decoupling search index: the essentials.

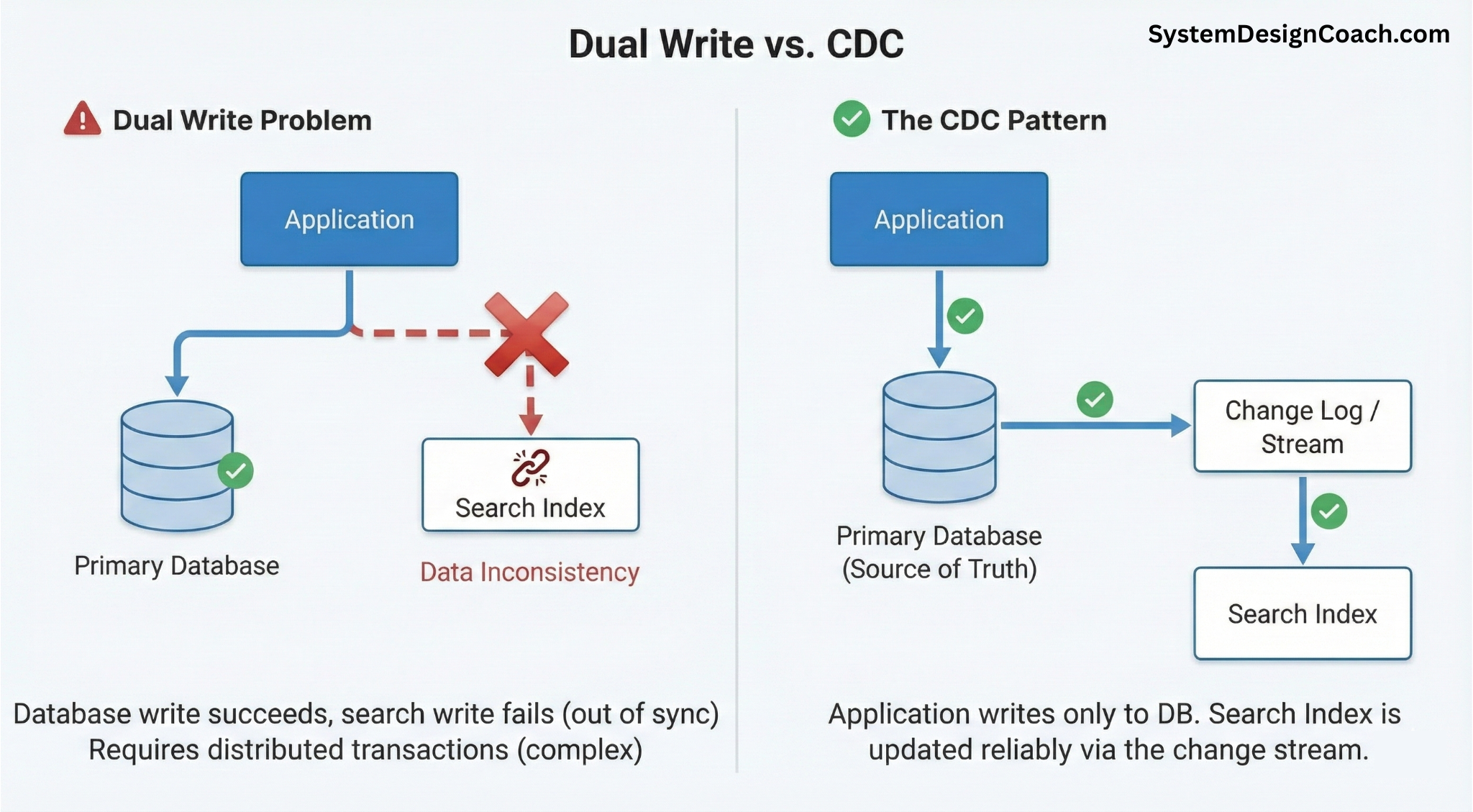

When teams first introduce a search index, a common instinct is to have the application code to update both the primary database and search index in the same request. On a small scale, this often appears to work. On a production scale, however, it becomes one of the most common sources of data inconsistency. This is because updating the database and updating the search index are two independent operations. Each can fail, succeed, or time out independently. To make this approach work for all cases, you would need a distributed transaction, effectively a two-phase commit, spanning the database and the search system. In practice, this often leads to fragile, hard-to-debug systems.

A more robust approach is to stop treating the search index as a peer write target and instead treat it as a derived view of the database. This is where Change Data Capture (CDC) comes in.

With CDC, the database remains the single source of truth. Every committed change, insert, update, or delete, is captured from the database's internal change log and emitted as an ordered stream of events. The search index then consumes this stream asynchronously and updates itself based on what actually committed in the database, rather than what the application attempted to write.

In the following sections, we'll look at how this CDC-based approach works in practice and what design considerations matter when keeping a search index reliably in sync at scale. We will break it down into three key components:

- Baseline Architecture: The standard data flow for DynamoDB and PostgreSQL.

- Consistency: Solving race conditions and out-of-order events with external versioning.

- Resilience: Managing backpressure, retries, and "poison pills."

1. Baseline Architecture and Data Flow

To understand how to build a resilient system, we must first establish the baseline architecture. Before we tackle edge cases, race conditions, and failures, let's map out the standard data flow for the two most common infrastructure patterns: NoSQL (DynamoDB) and Relational (PostgreSQL).

CDC Flow with DynamoDB

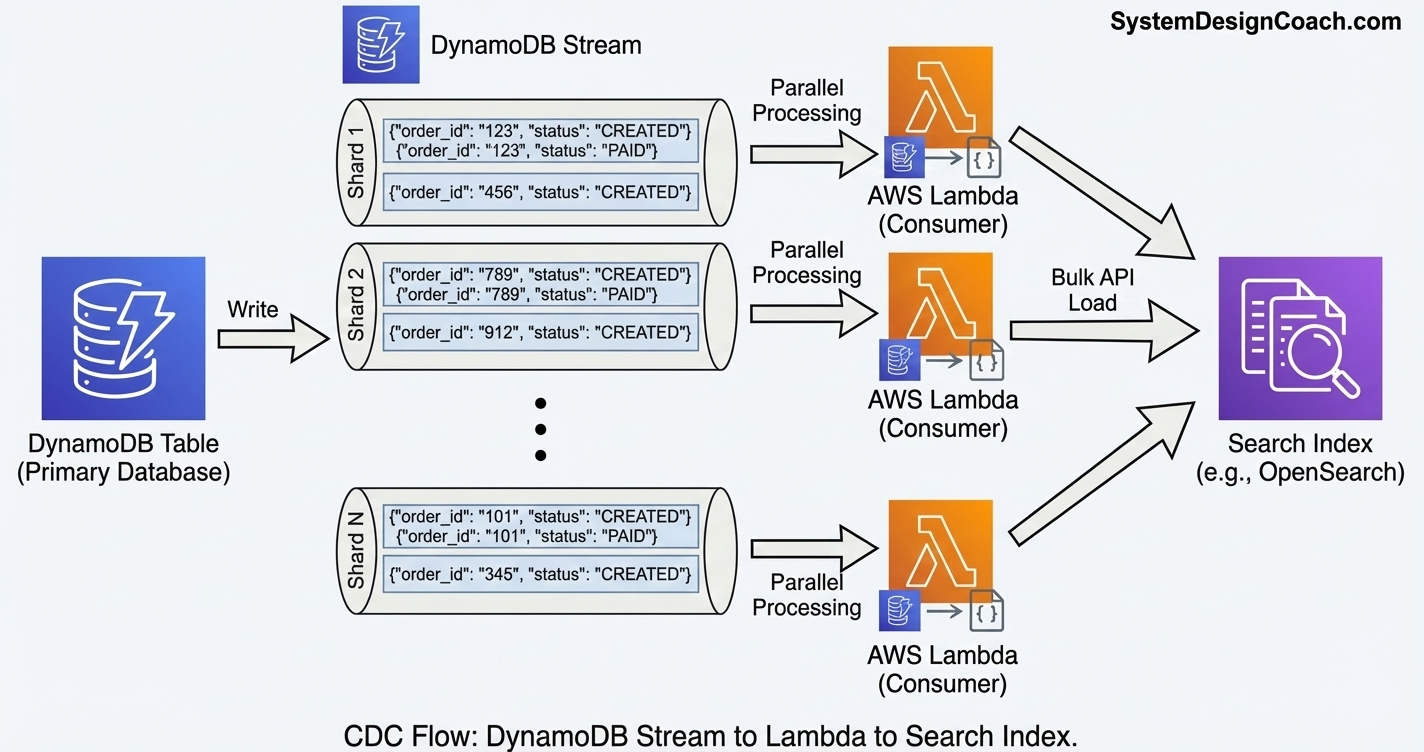

If you are using DynamoDB as your database, you can use DynamoDB Streams to catch changes and Lambda to send the update to search index.

Enable DynamoDB Stream on your table: When a stream is enabled on a table, DynamoDB records every successful insert, update, and delete into an internal change log. Each change is emitted as an event that contains the primary key, metadata about the operation, and depending on configuration, the state of the item before and after the change. These events are stored in an ordered stream, with ordering guaranteed for each partition key. This means that all updates for the same partition key (e.g. order_id 123) are delivered in sequence, but across different items can be interleaved.

For example, assume an order with order_id=124 goes through state transitions like CREATED → PAID → SHIPPED → DELIVERED in that sequence. At the same time, another order with order_id=456 goes through the same state transitions. In DynamoDB stream, the events across the two orders may be interleaved, but updates for the same order will never be out of sequence as illustrated below:

t1: order_id=123 status=CREATED t2: order_id=456 status=CREATED t3: order_id=123 status=PAID t4: order_id=123 status=SHIPPED t5: order_id=456 status=PAID t6: order_id=123 status=DELIVERED

Connect an AWS Lambda consumer to the stream: You can configure a Lambda to poll the stream using the table stream's unique resource name (ARN) and receive records in batches, typically ranging from 100-1000 changes at a time. DynamoDB Streams are internally partitioned into shards, and items within the same shard are guaranteed to be in sequence. So, Lambda can safely process these shards in parallel, with one Lambda instance handling records from a given shard at any point in time.

Transform and load into Search Index: Inside the Lambda function, you iterate through the batch to transform the data. This involves converting DynamoDB's internal, typed JSON format into standard JSON documents suitable for your search schema. Finally, the Lambda sends these JSON documents to the search index as batches (e.g. 100-1000 records at a time) using the Bulk API. Writing updates in bulk significantly reduces network and indexing overhead and improves throughput, especially under high write rates.

CDC Flow with PostgreSQL

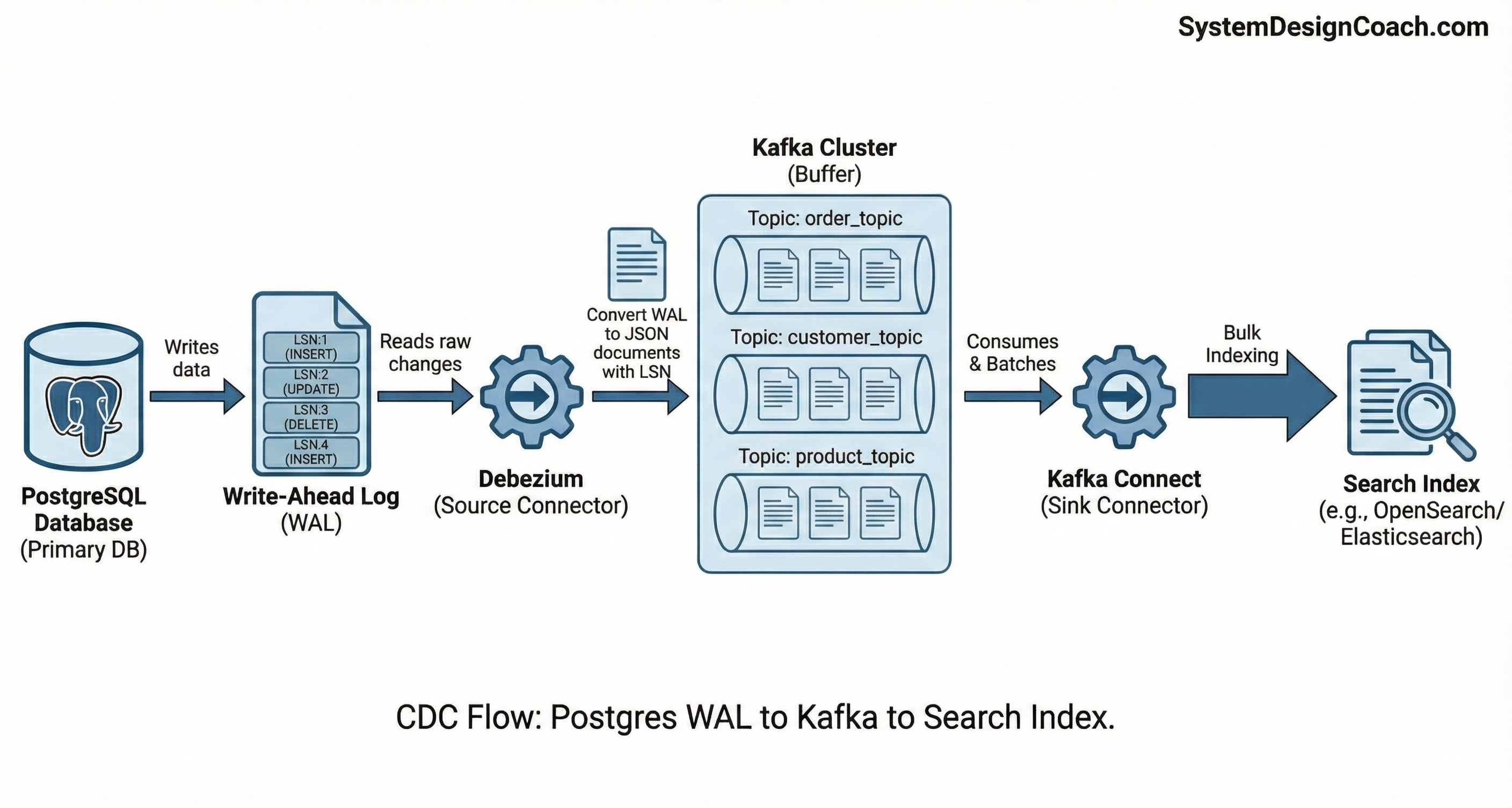

Unlike DynamoDB, relational databases like Postgres don't emit change events directly. However, they record every change internally as part of its durability guarantees. Change data capture for Postgres builds on this foundation by turning the database's internal change log into a reliable event stream.

The WAL (Write-Ahead Log): Postgres writes every committed change, insert, update or delete, to a local file called the WAL before the data is applied to table files. This mechanism ensures crash recovery, but it also gives us a complete, ordered record of everything that actually committed to the database. In a CDC architecture, the WAL becomes the source of truth for downstream systems.

Debezium: This is a specialized tool that continuously "tails" the WAL. It reads the raw database log entries and converts them into clean, standardized change events. Each event includes the affected row, the type of operation, and crucial metadata such as the Log Sequence Number (LSN), which uniquely identifies the position of the change in the WAL.

Kafka: Debezium pushes these events into Kafka, typically with one topic per table (or per logical grouping). Kafka serves as a durable, scalable buffer between the database and downstream systems. This decoupling is critical: if the search index slows down or goes offline temporarily, the database continues operating normally while Kafka safely retains the backlog of changes.

The Consumer: A downstream consumer reads events from Kafka and applies them to the search index (Elasticsearch or OpenSearch). This consumer can be implemented using a Kafka Connect sink connector or a custom service. Updates are commonly batched and written using bulk APIs to maximize throughput.

If you are running Postgres on Amazon Aurora, you don't need to manage the raw WAL files or the Debezium servers yourself. The CDC pipeline can be streamlined using AWS-managed services:

- Logical Replication Slots: In Aurora, you enable Logical Replication, which exposes a logical stream of committed changes derived from the WAL. This instructs Aurora to retain change records until they are consumed.

- Amazon MSK Connect (Debezium runtime): Instead of running Debezium on your own servers, you can use MSK Connect. It's a serverless way to run Debezium that automatically handles scaling, restarts and failure recovery.

- Amazon MSK (managed Kafka): This provides the same durability and buffering as Kafka but without the operational burden of managing brokers and ZooKeepers.

- Kafka to Search Index: You still need a downstream consumer (for example, a Kafka Connect sink connector, a custom service, or a Lambda function) to read change events from Kafka and apply them to the search index.

Because Aurora separates compute from storage, reading changes through logical replication has negligible impact on write performance even under heavy load.

2. Maintaining Consistency: Protecting Against Out-of-Order Updates

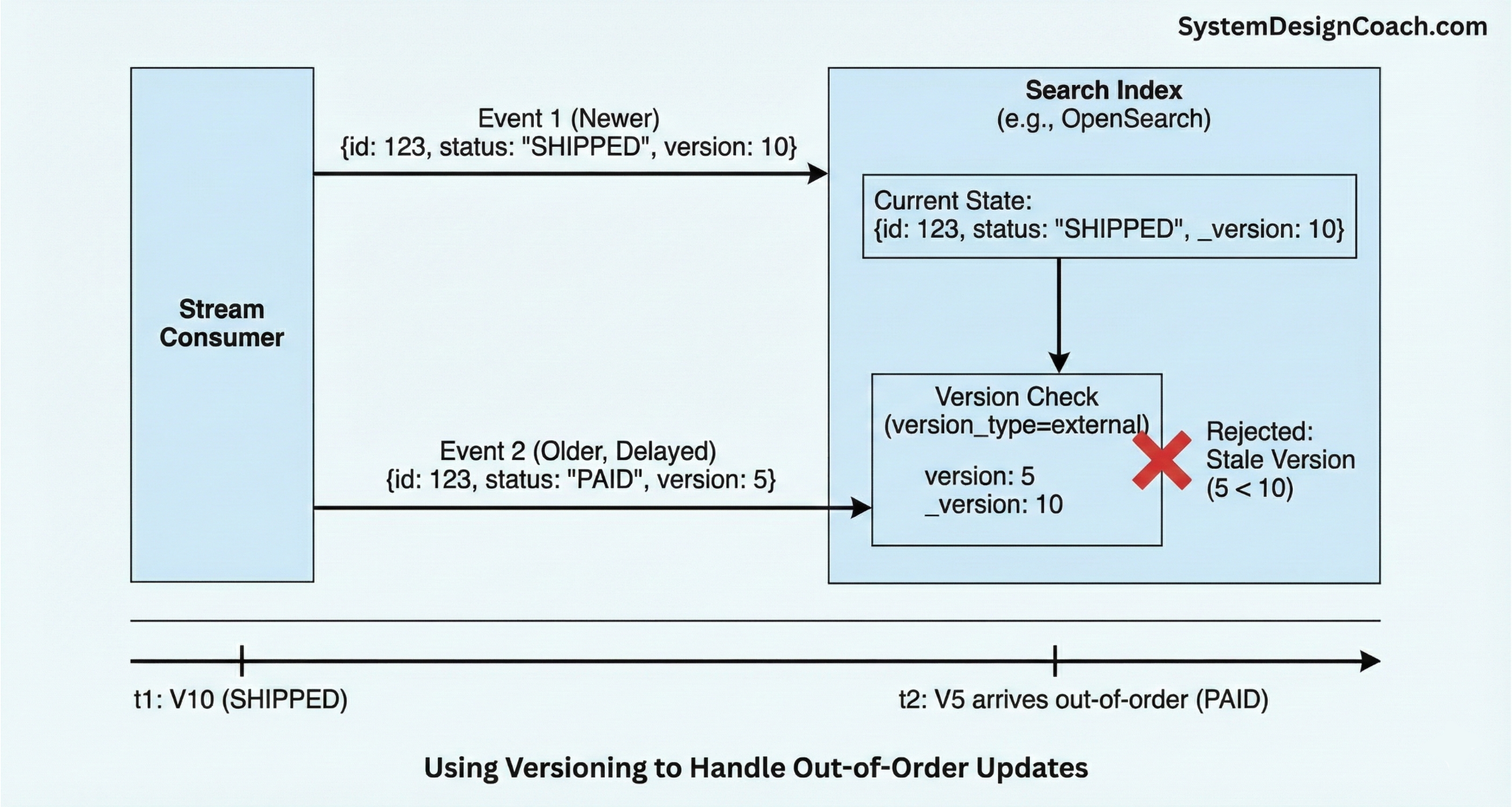

When keeping a search index in sync with a database, one common concern is out-of-order delivery: an older update arriving after a newer one and overwriting correct data in the index.

Both DynamoDB Streams and PostgreSQL CDC already provide strong ordering guarantees:

- DynamoDB Streams preserves order for updates to the same partition key.

- PostgreSQL WAL provides a total order of committed changes via monotonically increasing LSNs.

In practice, this means events for the same record normally arrive in sequence. However, real production systems still face issues like partial failures and consumer restarts. These scenarios can cause older events to be replayed after newer ones. For this reason, production systems add a simple but powerful safety net: external versioning.

Instead of blindly applying every update, each write to the search index includes a version that represents the recency of the change. Elasticsearch and OpenSearch support this natively via the version_type parameter. Specifically, when sending a bulk update request, you can set version_type=external. This way, if an update arrives with version 5 but the index already contains version 10, the update is rejected automatically. This prevents stale data from overwriting fresh data.

Choosing the Version Source

DynamoDB: A common choice is the ApproximateCreationDateTime from DynamoDB Streams or an explicit version attribute stored in the item. Although the name sounds imprecise, it is safe for this purpose: for updates to the same partition key, these timestamps are strictly increasing and reflect the commit order of stream events. "Approximate" here refers to wall-clock precision, not ordering correctness.

PostgreSQL: For Postgres, the WAL's Log Sequence Number (LSN) is an ideal version. LSNs are monotonically increasing and precisely represent commit order. Debezium exposes this value directly, making it easy to pass through Kafka and use as the external version when indexing.

In short, ordering guarantees of DynamoDB and Postgres handle the common case. External versioning protects you from the edge cases. Together, they turn search synchronization from "usually correct" into provably correct under retries and failures.

3. Building for Resilience

In a production system, failures are inevitable. Lambda functions can crash, consumers can fall behind, and search clusters may be throttled or taken down for maintenance. A robust sync pipeline must be able to absorb these failures without losing data or blocking progress.

Building a truly resilient pipeline rests on four key pillars: decoupling, smart retries, active flow control, and failure isolation.

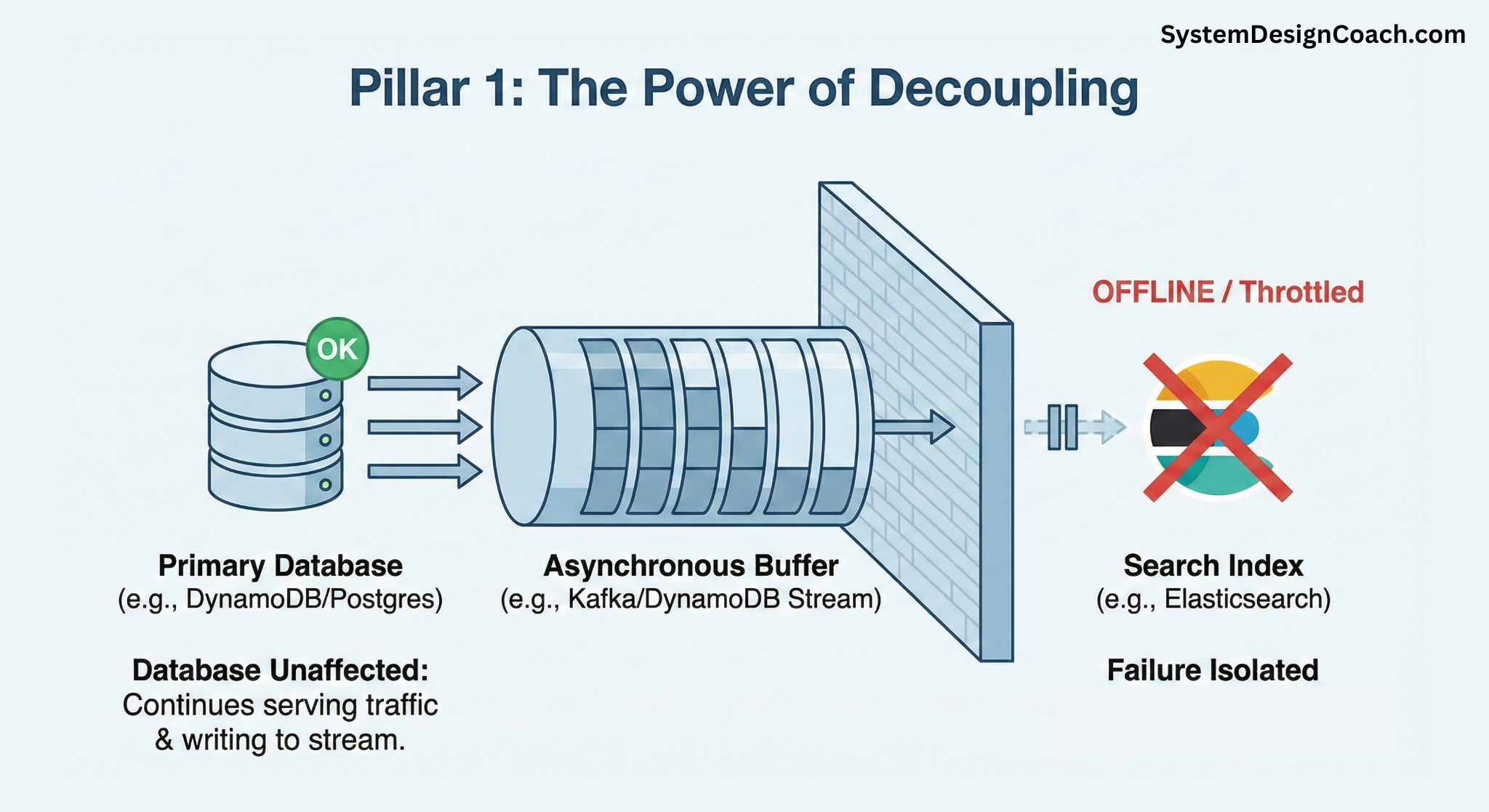

Pillar 1: The Power of Decoupling

The single most important resilience feature is already built into the architecture: the asynchronous buffer. Whether it's a Kafka topic or a DynamoDB Stream, this buffer decouples the database from the search index. If Elasticsearch goes offline for an hour, your primary database isn't impacted. It continues to serve traffic and record changes into the stream. Once the search index recovers, the consumer simply picks up where it left off and works through the backlog.

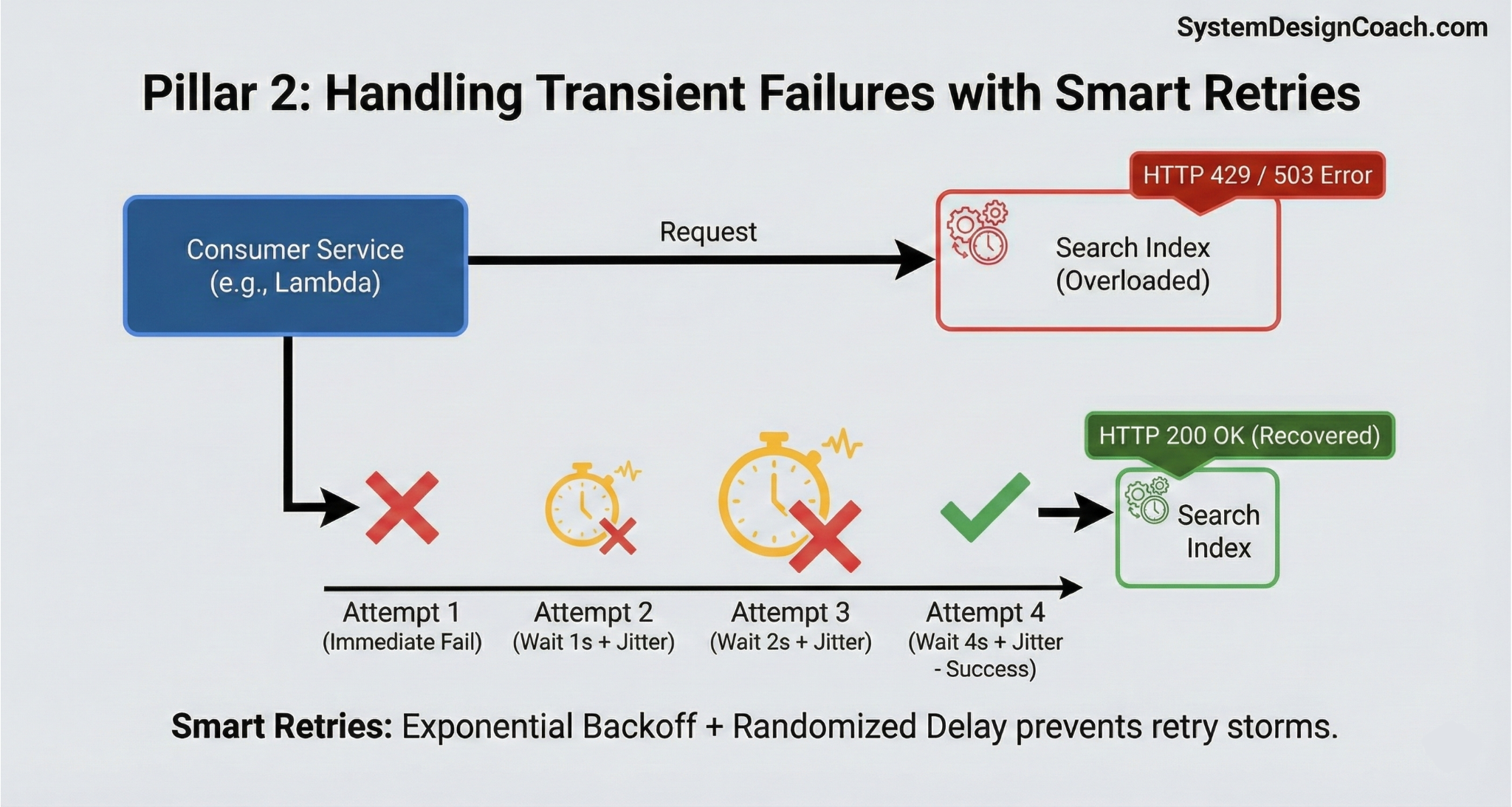

Pillar 2: Handling Transient Failures with Smart Retries

Transient failures, like a brief network glitch or a 429 Too Many Requests response from an overloaded search cluster, should be handled with retries. However, naive retries can lead to a "retry storm" that further overwhelms a struggling system.

Treat HTTP 429 or 503 responses as explicit backpressure signals to slow down. Never retry immediately; instead, use exponential backoff (e.g., wait 1s, 2s, 4s) combined with jitter (randomized delay). This gives the downstream system breathing room to recover and prevents all consumers from hammering the API at the exact same millisecond.

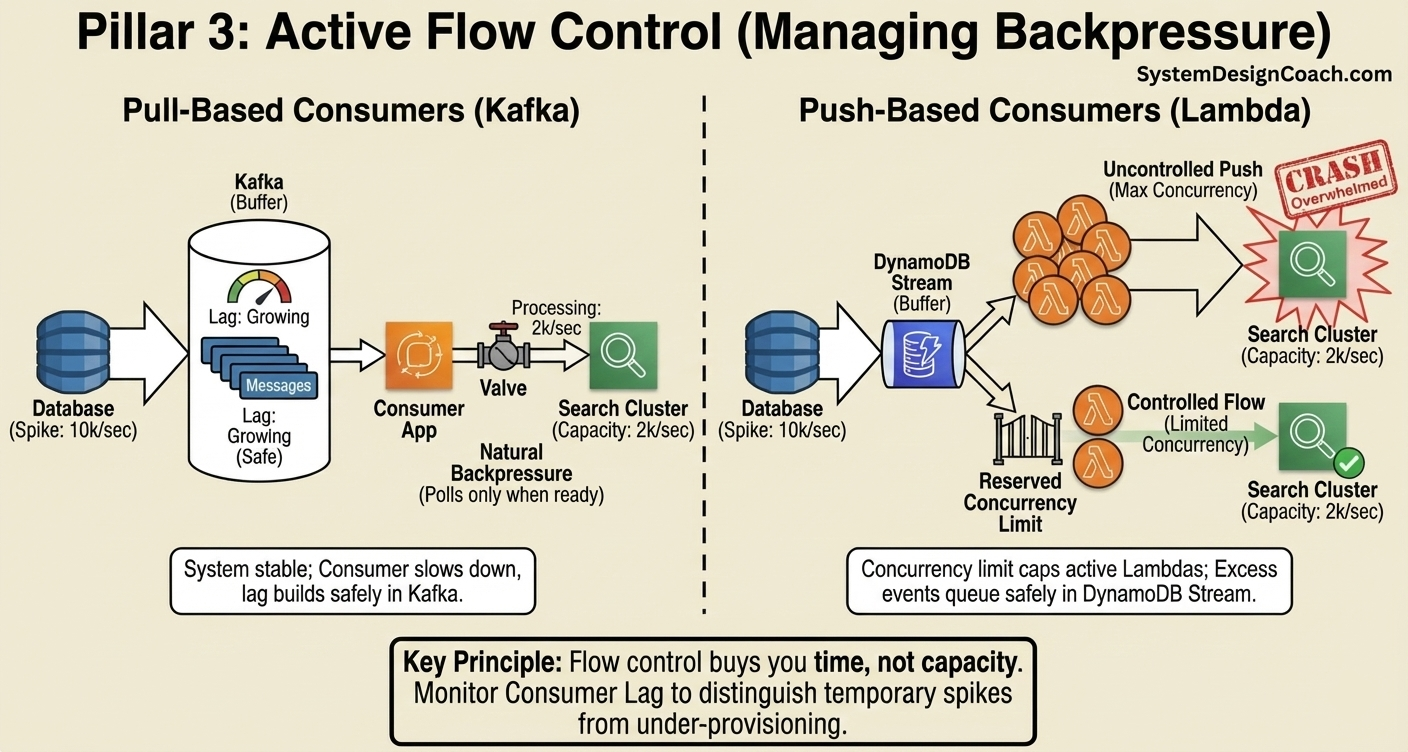

Pillar 3: Active Flow Control (Managing Backpressure)

What happens when your database spikes to 10,000 writes per second, but your search cluster can only index 2,000? If this is a permanent state, you simply need a bigger search cluster. But for traffic spikes, maintenance windows, or periodic batch jobs, you need flow control to ensure the backlog builds up safely in your buffer without crashing the downstream system.

Pull-Based Consumers (Kafka): This model handles backpressure naturally. Your consumer application polls Kafka, processes a batch, and only then polls for more. If the search index slows down, the consumer slows down. The "lag" (unprocessed messages) will grow in Kafka, but the system remains stable and will drain the backlog once the spike passes.

Push-Based Consumers (Lambda): By default, Lambda processes each DynamoDB Stream shard with up to one concurrent consumer, though this can be increased using the ParallelizationFactor setting. While this maximizes throughput, it can be risky when the downstream search system is capacity-constrained. In this scenario, Lambda may scale up aggressively to match a high write rate (for example, 10k updates per second), overwhelming the search cluster. To prevent this, you can configure a reserved concurrency limit on the function. This caps the number of active Lambda instances, forcing excess events to queue safely in the DynamoDB Stream (which allows data retention for up to 24 hours) rather than overwhelming the search API.

In short, Flow control buys you time, not capacity. You must monitor Consumer Lag. If the lag grows temporarily and auto-recovers, your flow control is working. If the lag grows indefinitely, your search cluster is under-provisioned, and you must scale it up.

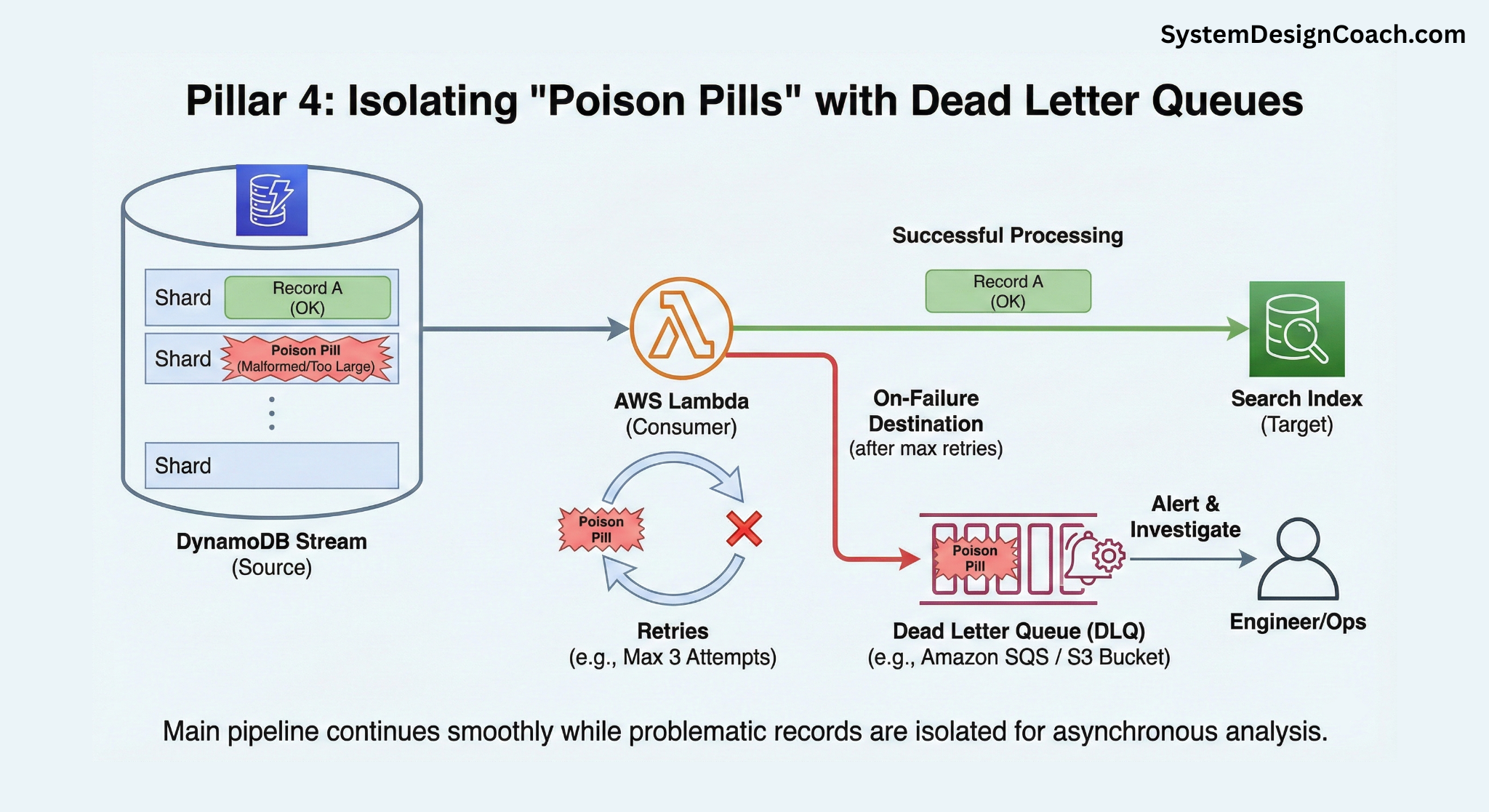

Pillar 4: Isolating "Poison Pills" with Dead Letter Queues

Not all failures are transient. Sometimes a specific record may consistently fail because it is fundamentally unprocessable; for example, it contains malformed data or exceeds the search index's document size limit. This is a "poison pill." If you retry it indefinitely, it will block processing for its entire shard or partition.

The solution is to detect and isolate these failures:

- Configure a Retry Limit: Set a reasonable maximum number of retries (e.g., 3-5 attempts).

- Use a Dead Letter Queue (DLQ): If a record fails all retry attempts, the system should automatically move it to a separate storage location, such as an Amazon SQS queue or an S3 bucket.

- Alert and Investigate: Set up alerts on the DLQ. This allows engineers to investigate the problematic data asynchronously and decide whether to fix and replay it or discard it, all while the main pipeline continues to flow smoothly.

For Lambda consuming DynamoDB Streams, this behavior is configurable natively. You can specify a maximum retry attempt and an on-failure destination (DLQ) for discarded records.

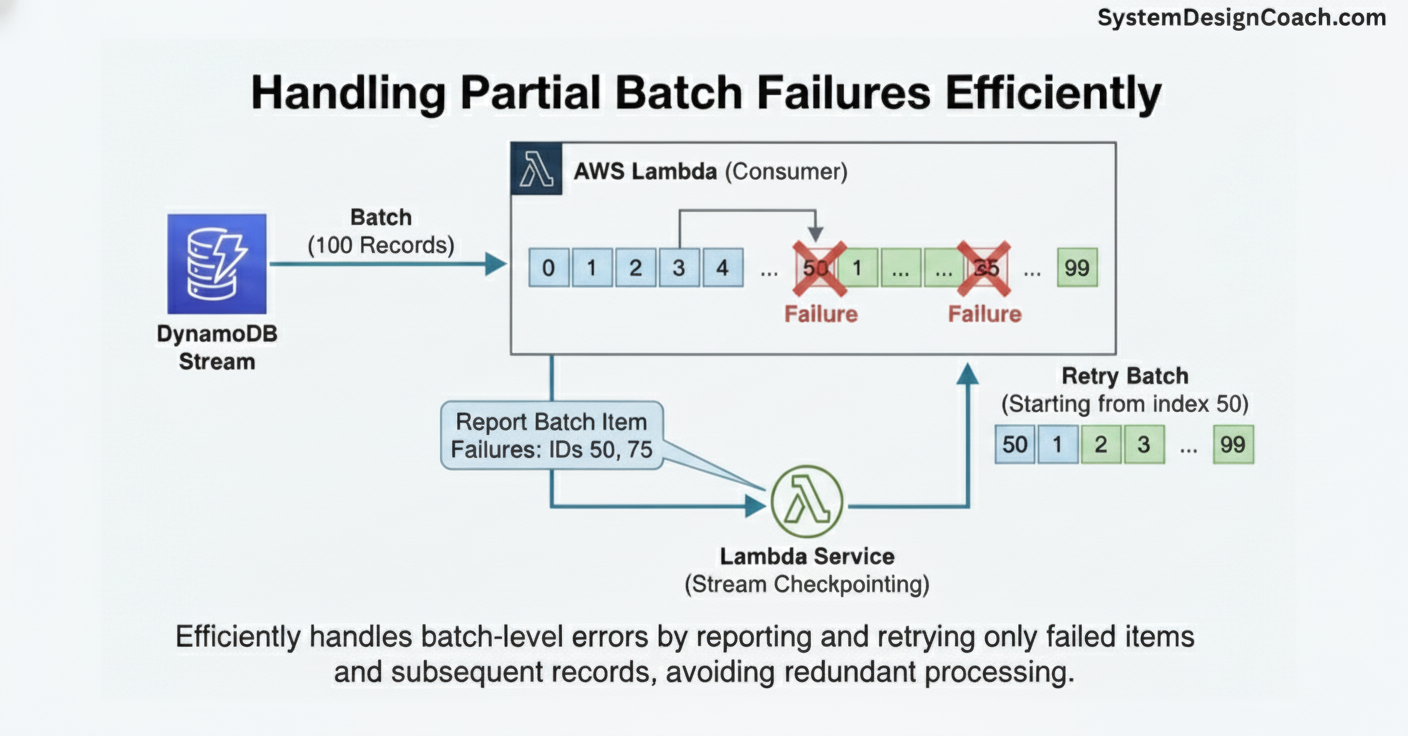

In addition to the abovementioned four pillars, you can have mechanisms to handle partial batch failures efficiently. When processing records in batches for efficiency, a common pitfall is failing the entire batch because of one bad record. This is inefficient and exacerbates retry loops.

Modern tools solve this. For example, when using Lambda with DynamoDB Streams, you should configure your function to report batch item failures. If a batch of 100 records has failures at index 50 and 75, your Lambda can return just those item IDs. The Lambda service will checkpoint the stream after the last successful record and only retry the failed items and those that followed them (meaning it skips records 0-49 and restarts processing precisely from record 50).

Key Takeaways

- Do not dual-write to your database and search index. Treat the search index as a derived view, not a peer write target.

- Change Data Capture (CDC) is the safest way to keep search in sync because it reflects what actually committed, not what the application intended.

- DynamoDB Streams preserve ordering per partition key; PostgreSQL WAL provides a total order via LSNs.

- External versioning is essential. Ordering guarantees handle the common case; versioning protects you from retries, replays, and partial failures.

- Backpressure is unavoidable at scale. Use buffers, flow control, and concurrency limits to absorb spikes without outages.

- Dead Letter Queues and partial batch handling prevent single bad records from stalling the pipeline.

Summary

We've covered three essential building blocks for keeping your search index in sync with your database using Change Data Capture:

- Baseline Architecture: How DynamoDB Streams and PostgreSQL WAL enable CDC, and how to set up the fundamental data flow patterns.

- Consistency: Using external versioning to protect against out-of-order updates and ensure data integrity.

- Resilience: Building robust pipelines with decoupling, smart retries, flow control, and dead letter queues.

Together, these three pillars form a solid foundation for CDC-based search synchronization. However, there are additional production considerations to address: how to handle data drift through reconciliation, how to bootstrap your search index with existing data, and when to use managed services versus custom solutions.

Continue reading: Keeping your search index in sync with your primary database (Part 2) →